Measles, a highly contagious but preventable disease, is re-emerging in pockets of the United States, warning of the dangers of a growing anti-vaccine movement.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recorded more cases this year than the 58 recorded in all of 2023, though the agency is not expected to release exact numbers until Friday. On Monday, the agency advised health care providers to ensure unvaccinated patients, especially those traveling internationally, stay current on their vaccinations.

The number of cases is likely to continue to rise because of a strong outbreak of measles worldwide, along with spring travel to some areas with outbreaks, including Britain, said Dr. Manisha Patel, chief medical officer in the CDC’s division of respiratory diseases.

Almost all cases in the United States so far have been linked to unvaccinated travelers. “We’re not going to see widespread measles cases across the country,” said Dr. Patel. “But we expect additional cases and outbreaks to occur.”

Measles is one of the most contagious diseases. Each infected person can spread the virus to up to 18 others. The virus is airborne and can remain aloft for up to two hours after an infected person has left the room, spreading rapidly through homes, schools and childcare facilities.

In Chicago, a measles case at an immigrant shelter rose to 13, prompting the CDC to send a team to help contain the outbreak. (Two additional cases in the city appear to be unrelated.)

In Florida, seven students at an elementary school contracted measles, even as the state’s surgeon general, Dr. Joseph Ladapo, left it up to parents to decide whether unvaccinated children should attend school.

In southwest Washington, officials found measles in six unvaccinated adult members of a family living in two counties. And in Arizona, an international traveler infected with measles dined at a restaurant and spread the virus to at least two others.

Measles was eliminated in the United States in 2000, and American children generally must be vaccinated to attend school. However, sporadic outbreaks lead to larger outbreaks every few years. But now a drop in vaccination rates, exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic, has experts worried about a resurgence.

When vaccinations are delayed, “the first disease to show up is measles because it’s highly contagious,” said Dr. Saad Omer, dean of the O’Donnell School of Public Health at UT Southwestern in Dallas.

Nine out of 10 unvaccinated people in close contact with a measles patient will become infected, according to the CDC

Measles is much less deadly in countries with high vaccination rates and good medical care. Fewer than three in 1,000 children in America with measles will die as a result of serious complications such as pneumonia or encephalitis, swelling of the brain.

However, about one in five people with measles may end up in hospital.

Because widespread measles outbreaks have been rare, most Americans, including doctors, may not recognize the bright red rash that accompanies respiratory symptoms in a measles infection. They may have forgotten the impact of the disease on individuals and communities.

“Most of the people in our local health department have never seen a measles outbreak,” said Dr. Christine Hahn, Idaho’s state epidemiologist, who contained a small cluster of cases last year.

“It will be a big challenge for us to respond if and when we have our next outbreak,” he said.

Before the introduction of the first measles vaccine in the 1960s, the disease killed an estimated 2.6 million people worldwide each year. But its full impact may have been much greater.

Measles cripples the immune system, allowing other pathogens to more easily enter the body. A 2015 study estimated that measles may account for half of infectious disease deaths in children.

For about a month after the acute illness, measles can blunt the body’s first response to other bacteria and viruses, said Dr. Michael Mina, chief scientist at digital health company eMed and former epidemiologist at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. .

That leaves patients “massively susceptible to bacterial pneumonia and other things,” said Dr. Mina, who was lead author of the 2015 study.

“It’s very dangerous for people in those first few weeks after measles,” he added.

The virus also causes a kind of amnesia of the immune system. Normally the body “remembers” the bacteria and viruses it has fought in the past. Dr. Mina and colleagues showed in 2019 that people with measles lose between 11 and 73 percent of their hard-won immune repertoire, a loss that can last for years.

This does not mean that the body no longer recognizes these pathogens at all, but it shrinks the arsenal of weapons available to fight them.

“People need to know that if they choose not to vaccinate, that’s the position they’re putting themselves and their family in,” Dr Mina said.

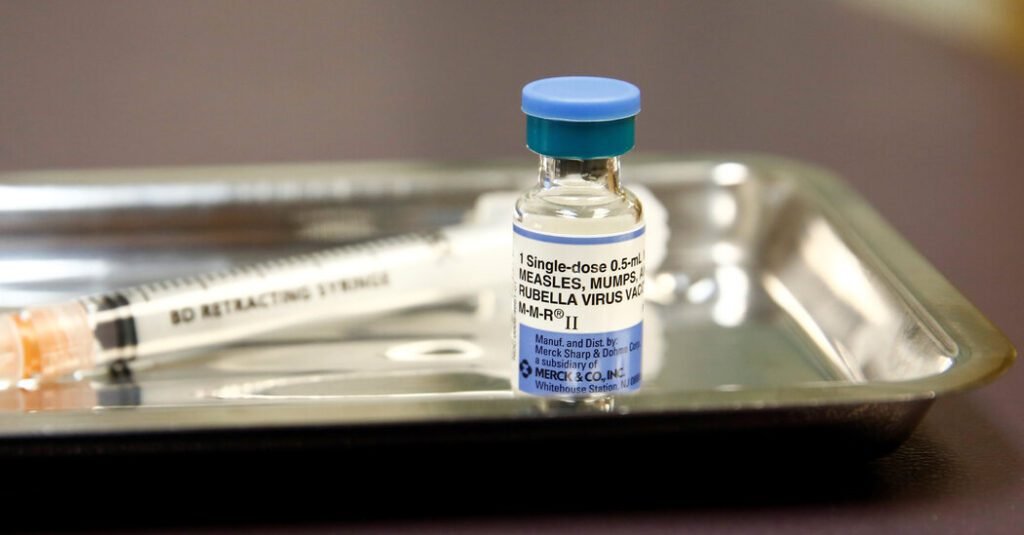

The CDC recommends getting the first dose of measles vaccine after 12 months of age and a second dose between 4 and 6 years of age. Even one dose of the vaccine is 93 percent effective. Measles vaccination prevented 56 million deaths between 2000 and 2021, according to the World Health Organization.

Vaccination rates in the United States have shown a distinct, albeit small, drop to 93 percent in the 2022-23 school year from 95 percent in 2019-20 — the level needed to protect everyone in the community. Vaccination exemption rates increased in 40 states and the District of Columbia.

In a survey last year, just over half of Republicans said public schools should require measles vaccinations, compared with about 80 percent before the pandemic. (Support for vaccines among Democrats has remained steady.)

While national or state vaccination rates may be high, there may be pockets of low immunization that provide a breeding ground for the measles virus, Dr. Omer said.

If there are enough unvaccinated cases to sustain the outbreak, even those who have been vaccinated but whose immunity may have weakened are vulnerable, he said.

In Idaho, 12 percent of kindergartners have no vaccination history. Some of the gap results from parents being unable or unwilling to share records with schools, not because their children have not been vaccinated, Dr. Hahn said.

But online schools, which have proliferated through the pandemic and remain popular in the state, have some of the highest vaccine exemption rates, he said.

In September, a young man from Idaho brought back measles after international travel and became ill enough to be hospitalized. Along the way, it exposed fellow passengers on two flights, dozens of health care workers and patients, and nine unvaccinated family members. All nine developed measles.

Idaho was “very lucky” with the outbreak because the family lived in a remote area, Dr. Hahn said. However, it is very likely that there are many other areas in the state where an outbreak would be difficult to contain.

“We have plenty of tinder, if you will,” he added.

Some large outbreaks in recent years have erupted among large groups of unvaccinated people, including the Amish in Ohio and the Orthodox Jewish community in New York.

In September 2018, an unvaccinated child returned to New York from Israel, carrying the measles virus contracted during an outbreak in that country.

Although the city maintains high vaccination rates, that case sparked an outbreak that raged for nearly 10 months, the largest in the country in decades. The city has declared a public health emergency for the first time in more than 100 years.

“We had more than 100 chains of transmission,” said Dr. Oxiris Barbot, the city’s health commissioner at the time, and now president and CEO of the United Hospital Fund.

“Keeping it all straight was a challenge,” he recalls. “And to have to research over 20,000 such reports, that was huge.”

Working with community leaders, city officials hastily administered about 200,000 doses of vaccine. More than 550 city staff members were involved in the response, and the final cost to the city’s health department exceeded $8 million.

The CDC is working with state and local health departments to identify pockets of low vaccination and prepare them for outbreaks, Dr. Patel said. The agency is also educating health care providers to recognize the symptoms of measles, particularly in patients with a history of international travel.

Measles is a slippery adversary, but public health is well-acquainted with the tools needed to contain it: screening, contact tracing, and vaccination of the susceptible.

“We are not helpless bystanders,” said Dr. Omer. “The focus should be on public health based on meat and potatoes.”