There is a shift underway in Asia that is reverberating through global financial markets.

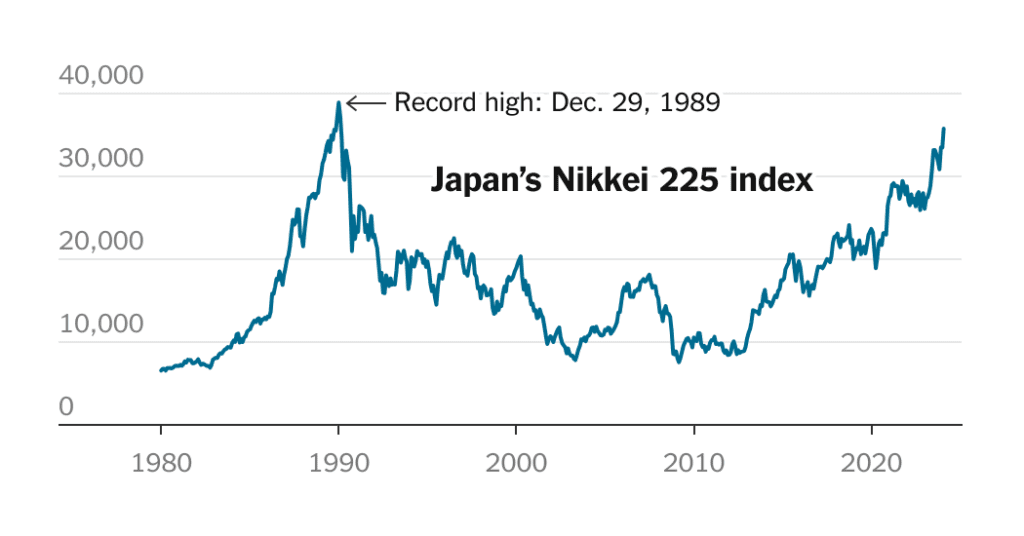

Japan’s stock market, ignored by investors for decades, is making a furious comeback. The benchmark Nikkei 225 is inching closer to the record it hit on Dec. 29, 1989, which effectively marked the peak of Japan’s economic boom before a collapse that led to decades of low growth.

China, a market that has long been impossible to ignore, is moving downwards. Shares in China recently hit lows not seen since the fall in 2015, and Hong Kong’s Hang Seng index was the world’s worst-performing major market last year. Stocks only fell when Beijing recently signaled its intention to intervene, but remain well below previous highs.

This year was set to be a tumultuous one for global markets, with unpredictable swings as economic fortunes diverge and voters in more than 50 countries head to the polls. But there is an unforeseen twist already underway: a shift in investor perception of China and Japan.

Taking advantage of this shift, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida addressed more than 3,000 global financiers gathered in Hong Kong this week for a conference sponsored by Goldman Sachs. It was the first time a Japanese prime minister had given a keynote address at the event.

“Japan now has a golden opportunity to completely overcome the low economic growth and a deflationary environment that have persisted for a quarter of a century,” Mr. Kishida said in a video recording. His government, he said, “will demonstrate to all of you Japan’s transition to a new economic stage by mobilizing all policy tools.”

It’s the kind of message Japan has been honing for a decade, and now investors want to hear more of it. Foreign investors poured $2.6 billion into the Japanese stock market last week, up from $6.5 billion the previous week, according to Japan Exchange Group data. That’s a sharp shift from the roughly $3.6 billion blocked in December.

All that money has sent Tokyo’s Nikkei 225 up about 8% this month. The market is up more than 30 percent in the past 12 months. This week, Toyota hit a record market value for a Japanese company of about $330 billion, surpassing the mark set in 1987 by telecommunications group NTT.

A combination of factors has contributed to Japan’s recent success. A weak yen has made stocks look cheap to foreign investors and has been a boon to exporters and Japan-based multinationals that make their profits overseas. Major reforms in the corporate sector have given shareholders more rights, enabling them to demand changes in strategy and management. Unlike inflation in other parts of the world, rising inflation in Japan is a sign that things are moving in the right direction, after decades of falling prices and sluggish economic growth have dampened the appetite among consumers and companies to spend. .

And there is an additional factor: geopolitics. The longer-term outlook for Japan, the third-largest economy, looks good as parts of the world deteriorate in the second-largest economy, China.

“One of the best things to happen to Japan is China,” said Seth Fischer, founder and chief investment officer at Oasis Management, a Hong Kong-based hedge fund.

“Japan has been working for 10 years to create a more productive corporate environment and a better place to be an equity investor through the continuous effort to improve value,” Mr. Fischer said. “People don’t feel the same way about China.”

In a recent survey of global fund managers by Bank of America, selling Chinese stocks and buying Japanese stocks were two of the three most popular trading ideas. (The other was to load up on high-flying American tech stocks.)

China’s ruling Communist Party has sought to intrude on the business sector in recent years, leaving investors concerned that politics often trumps the line for many of China’s corporate titans. The political and business ambiguity has also raised concerns in Washington and European capitals, leading to regulations that have prevented foreign investment in some sectors and companies.

China has not struggled for economic growth like Japan, but a prolonged housing market collapse has eroded consumer and investor confidence. Prolonged issues with China’s economy have exacerbated the weakness of the country’s currency, the yuan.

Much of the negative sentiment played out in Hong Kong, an open market where global investors have traditionally placed their bets on China and its companies. The market took a hit last year and fell further in the first three weeks of this year.

Beijing stepped in this week to try to reverse the sell-off. On Monday, the country’s No. 2 official, Premier Li Qiang, called on authorities to be more “dynamic” and take more measures to “improve market confidence.” His speech lifted stocks, as did a Bloomberg report, citing unnamed officials, that authorities were considering a bailout of the $278 billion market.

Then on Wednesday, the central bank, the People’s Bank of China, freed up commercial banks to do more lending, effectively pumping $139 billion into the market by reducing the amount of money banks are required to hold in reserve. Regulators also relaxed rules on how over-indebted property developers could repay loans.

Words and actions pushed the market higher this week, with the Hang Seng posting three of its best days this year. China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen markets also rebounded, though not as much.

But many investors say the measures have failed to address a much bigger problem: China’s economic trajectory. They remain disappointed with China’s response to its broader economic downturn and its perceived reluctance to deliver a spectacular stimulus, as it has done in previous periods of economic stress.

The Hang Seng fell 1.6 percent on Friday, reversing some of the week’s gains.

“We hope that will continue to happen,” said Daniel Morris, an analyst at BNP Paribas, referring to a more substantial effort to support markets. “But we have no confidence that it will happen. I honestly would have thought that at the end of last year all the bad news had to be weighed in, and yet we’ve fallen further this year.”

Economists, financiers and business executives around the world looked to China last year for an economic recovery after its government scrapped its “zero Covid” policy, punishing lockdowns that had at times brought the country to an economic standstill. But Chinese consumers have not engaged in the kind of “revenge spending” seen elsewhere since reopenings, and a property crisis has weighed on families, many of whom have nearly three-quarters of their savings tied up in real estate.

“There is not much confidence at home and then you have a government that is not very interested in supporting the economy,” said Louis Kuijs, chief Asia economist at S&P Global Ratings. “The markets were kind of expecting a lot more and they’re getting more disappointed and disappointed.”

And among the disappointed ranks are some Chinese investors, who are moving money to exchanges that track Japanese shares. At times the prices of these mutual funds trade well above the value of their underlying assets, a sign of investor excitement.