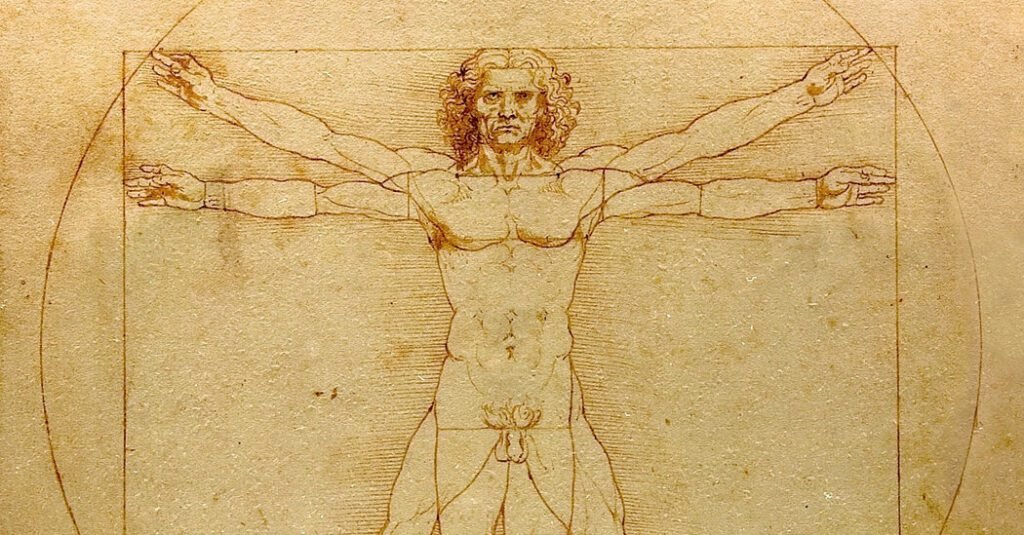

At the end of the 15th century, when the Italian Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci completed the “Vitruvian Man” – one of his most famous drawings, depicting the proportions of the human body – he could not have foreseen that it would be reproduced in cheap notebooks, brown . mugs, t-shirts, aprons, even puzzles.

Centuries later, the Italian government and German puzzle maker Ravensburger are fighting over who has the right to reproduce the “Vitruvian Man” and profit from it.

At the heart of the controversy is Italy’s cultural heritage and landscape code, which was passed in 2004 and allows cultural institutions such as museums to ask for concession fees and payments for the commercial reproduction of cultural goods such as the Vitruvian Man.

This code conflicts with European Union law, which states that works in the public domain (such as the “Vitruvian Man”) are not subject to copyright.

For more than a decade, Ravensburger sold a 1,000-piece puzzle featuring the famous design. But in 2019, the Italian government and the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, where the famous work and other da Vinci pieces are on display, used the Italian code to demand that Ravensburger stop selling the puzzle and pay a license fee .

Ravensburger refused and later argued that the Italian code did not apply outside Italy.

In 2022, a Venice court ordered the company to pay a fine of 1,500 euros (or about $1,630) to the government and the Gallerie dell’Accademia for each day it delays payment.

But last month, the legal battle took a turn when a court in Germany sided with Ravensburger, ruling that the company did not have to pay and that Italy’s heritage code did not apply outside its borders. The court said the Italian code violated European law that standardizes copyright protection for 70 years after the artist’s death. (Da Vinci has been dead for 505 years.)

“The Italian state does not have the regulatory authority to apply it outside Italian territory,” the German court ruled. “The contrary view violates the sovereignty of individual states and must therefore be rejected.”

But Italy kept pushing. An Italian government spokesman told an Italian news agency last week that the German decision was “abnormal” and that the government would challenge it before “every national, international and EU court”.

Italy’s Culture Ministry did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Heinrich Huentelmann, a spokesman for Ravensburger, said in a statement on Tuesday that the company remained in contact with the parties involved and was trying to resolve the conflict.

Ravensburger stopped selling the puzzle worldwide amid the legal battle, Mr. Huentelmann said, but a quick Google search revealed that similar puzzles made by other companies are still available online.

Eleonora Rosati, a lawyer and professor of intellectual property law at Stockholm University, said Italian officials were simultaneously trying to protect the country’s cultural heritage and capitalize on it.

Companies both inside and outside Italy that use pieces of Italian cultural heritage in products may want to tread carefully, Ms. Rosati said. He noted that in 2014 Italian officials went after an Illinois-based arms manufacturer for using an image of Michelangelo’s David statue to promote a rifle.

“I don’t think this German decision is the last word written on this matter, and indeed everyone who uses images of Italian cultural heritage may want to assess the risk they face in doing so,” Ms Rosati said. . “Right now, the situation has become quite heated.”

But Italy’s fervent approach to protecting culturally significant works could backfire, according to Geraldine Johnson, a professor of art history at the University of Oxford.

“The result may be that legitimate companies that could produce high-quality products depicting iconic Italian artwork will instead turn to non-Italian items,” Ms. Johnson said, noting that such a shift could reduce that the influence of Italian culture worldwide. while illegal knock-offs continue to be made cheaply with images deemed illegal by Italian courts.

“This does not seem to be in the best interest of increasing Italy’s global standing and relevance through the ‘soft’ power of iconic visual images,” he said.