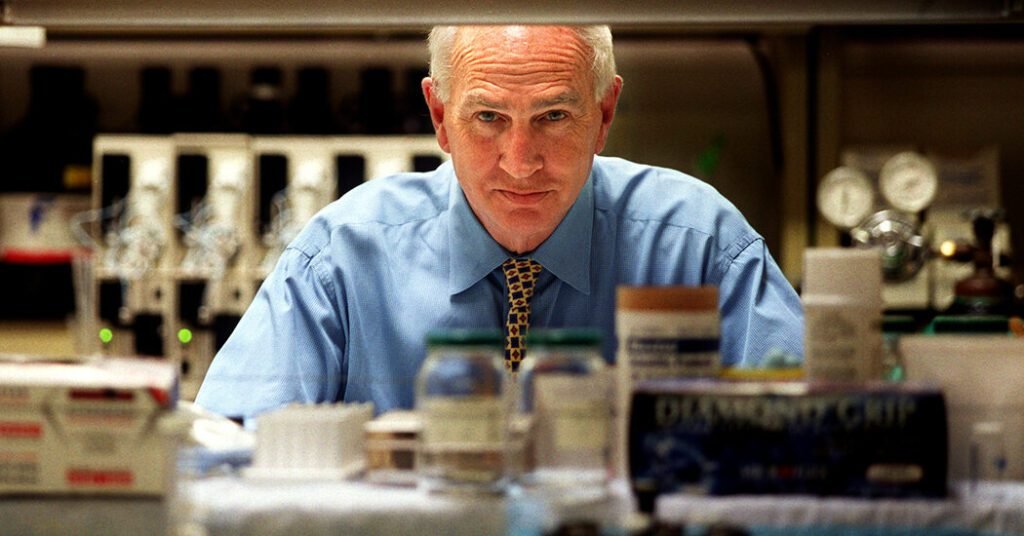

Dr. Don Catlin, who built the first U.S. anti-doping lab, and whose research unlocked the chemistry behind many previously undetectable performance-enhancing drugs and caught athletes cheating by using steroids and other banned substances, died Jan. 16 at his house in Los. Angels. It was 85.

Oliver’s son said the cause was a stroke. He also said his father had been diagnosed with dementia.

Dr. Catlin, sometimes called the father of drug testing in sports, was the director of UCLA’s Olympic Analytical Laboratory, which he started two years before the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles and led until 2007.

Over time, his lab tested up to 45,000 urine samples a year, looking for traces of banned substances in US Olympians. professional football players; college and minor league baseball players. and competitors in a FIFA World Cup.

“He was a towering legend,” Travis T. Tygart, chief executive of the United States Anti-Doping Agency, said in an interview. “His charm and stature at meetings of scientists and non-scientists allowed him to explain complex science to athletes and then put on his lab coat and work on carbon isotope ratio analysis.”

The quarter century of Dr. Catlin’s lab coincided with a period of drug scandals in the world of sports, including one involving Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson, who was stripped of his gold medal in the 100-meter race at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul. after testing positive for the anabolic steroid stanozolol.

Such controversy continued into the 2000s, with revelations that the Bay Area Laboratory Co-operative, or Balco, near San Francisco distributed steroids and illegal supplements to athletes, including baseball superstar Barry Bonds and track star Marion Jones . Also around this time, cyclist Lance Armstrong came back from cancer to win a record seven consecutive Tours de France using a banned substance regimen. He was eventually stripped of those titles.

As Dr. Catlin and the technicians in his lab worked diligently to catch cheaters and uncover new doping methods, he recognized that he was facing a Sisyphean task.

“I’m not saying it’s doomed, but we’re always playing catch-up,” he told New Scientist magazine in 2007. “I don’t see all the mass spectrometers and all the chemists in the world really being able to handle it. It’s becoming very expensive to develop tools to detect new drugs.”

Donald Hardt Catlin was born on June 4, 1938 in New Haven, Conn. His father, Kenneth, was an insurance executive. His mother, Hilda (Hardt) Catlin, ran the household.

After graduating from Yale University in 1960 with degrees in statistics and psychology, he was persuaded by a family friend, who was a surgeon, to study medicine. Five years later, he earned an MD from the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry.

From 1965 to 1968, he did an internship at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Medicine and another at the University of Vermont Department of Medicine before returning to UCLA as chief resident.

While in the US Army from 1969 to 1972, Dr. Catlin worked in internal medicine at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C. and, in his senior year, directed a treatment center for soldiers addicted to heroin while fighting in the Vietnam War. . He told USA Today in 2007 that he had clashed with Pentagon generals over his belief that addicts should be treated medically rather than jailed for turning to drugs.

“But they locked them up anyway,” he said.

After his dismissal, he joined the UCLA faculty as an assistant professor of pharmacology and medicine. An expert in pain management, he joined other researchers to publish a 1977 study of five patients that tested whether a morphine-like substance in the human pituitary gland could relieve pain and narcotic withdrawal symptoms.

In 1982 he became the first director of the Olympic anti-doping laboratory, with financial support of at least $1.5 million from the Los Angeles Olympic Organizing Committee. During the 1984 Summer Games there, at least 11 athletes tested positive for steroids.

Dr Catlin boosted the lab’s drug testing with research that boosted global efforts to clean up doping in sport.

In the late 1990s, he developed the carbon isotope ratio to determine whether an anabolic steroid is produced naturally in the body or derived from a banned substance, such as a synthetic steroid. In 2002, he discovered for the first time in sports the use of a form of EPO, or erythropoietin, that increases endurance by stimulating the production of red blood cells. Three gold medalists in cross-country skiing tested positive for the substance and were stripped of their medals.

Also in 2002, Dr. Catlin first detected a designer anabolic steroid, norbolethone, in an athlete’s urine after it was introduced to athletes at Balco by chemist Patrick Arnold.

“This was the first evidence that there were these brand-name drugs out there,” Dr. Catlin said in an interview at the time. “He told me that more will come.”

Then, in 2003, Dr. Catlin identified yet another designer steroid, tetrahydrogestrinone, or THG, after a syringe that was anonymously delivered to the United States Anti-Doping Agency was transferred to his laboratory.

It was a breakthrough as the active ingredient in ‘the clear’, a previously undetectable steroid Balco provided to many athletes. Barry Bonds testified in a federal grand jury that he received the “clear” and a testosterone-based cream from his trainer, but said he was told it was linseed oil and a pain reliever balm.

Jeff Novitzky, an Internal Revenue Service agent who began investigating the spread of performance-enhancing drugs in 2002, turned to Dr. Catlin after digging through Balco’s trash and collecting data posted online by Victor Conte Jr., the lab’s founder and president.

“I called him very early on and during this year he guided me through everything,” Mr. Novitzky said in an interview. “I had no idea what I was finding. In my trash, I found discarded drug wrappers, email communications from athletes, invoices for epitestosterone and it said the only reason to take epitestosterone is to beat a drug test. I could see the bells ringing in his head that something was going on.”

Dr. Catlin testified in 2003 to the grand jury that investigated Balko and Mr. Conte, who pleaded guilty to steroid distribution and money laundering. He served four months in prison. Mr. Bonds was convicted of obstruction of justice, but the conviction was overturned.

Dr. Catlin later discovered several other branded steroids, including methylandrostenol or mandole, the active ingredient in a subsequent iteration of “transparent” that was also found in a raid on the Balco lab.

After retiring from the UCLA lab, he went into business with his son Oliver to provide services such as customizing private drug testing programs for sports organizations, athletes and schools, as well as testing and certifying nutritional supplements and food products for banned substances and label claims . Dr. Catlin also continued related research and oversaw testing of human growth hormone, or HGH, at the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing.

In 2009, Dr Catlin agreed to run a strict and transparent anti-doping plan for Mr Armstrong, who had retired from cycling in 2005. But the plan was abandoned before Dr Catlin took a full blood and urine sample as the program was too complicated and too expensive, he told the New York Times at the time.

In addition to his son Oliver, Dr. Catlin has another son, Bryce, and two grandchildren. His wife, Bernadette (DeGroote) Catlin, died in 1989.

Dr Catlin said he felt an urgency to keep the Olympics, which he called “something natural and beautiful”, drug-free.

He told USA Today in 2007: “I can’t think of anything more exciting than the Olympic model, where 220 countries in the world participate and every four years they send their best to compete against the best from other countries and the best man or the woman wins . That’s wonderful. What could be nicer? Except it’s the drugs, idiot.”