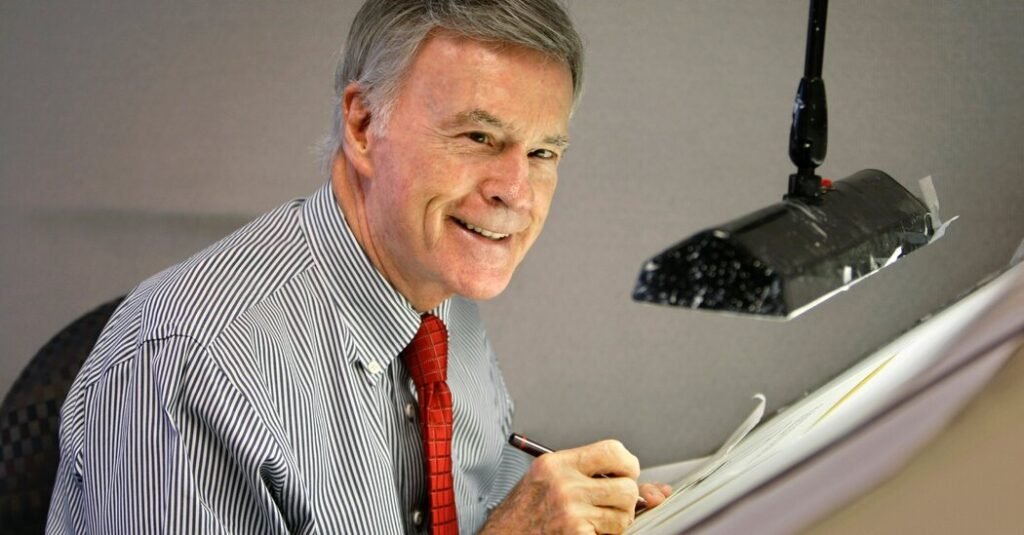

Don Wright, a two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist whose pointed work cut through duplicity and pomposity and resonated with common sense readers, died March 24 at his home in Palm Beach, Florida. He was 90 years old.

His death was confirmed by his wife, Carolyn Wright, a fellow journalist.

In a 45-year career, Mr. Wright drew about 11,000 cartoons for The Miami News, which folded in 1988, and then The Palm Beach Post, where he worked until he retired in 2008. But he reached a readership far beyond Florida: cartoons appeared in newspapers nationwide through syndication.

Mr. Wright’s readers knew where he stood, and especially what he was against, if it was the Vietnam War. Israel’s military support for the pro-apartheid regime in South Africa (depicted a menorah with missiles in place of candles). sexual abuse by clergy; the John Birch Society, the anti-communist fringe group; and racial divisions, notably the violent Ku Klux Klan.

The morning after he won his first Pulitzer, in 1966, Mr. Wright received a telegram from George G. Wallace, the segregationist governor of Alabama. “Sometimes even the worst cartoonists are unduly decorated for their work,” he said. “If the shoe fits, wear it.” Mr. Wright kept the telegram framed in his home.

This first award-winning cartoon – published during the Cold War, when the world was gripped by the fear of nuclear Armageddon – depicted two ragged men encountering each other in a barren, bomb-cratered landscape. “So,” they ask each other, “you were just bluffing?”

His 1980 Pulitzer-winning entry depicted two Florida state prison guards carrying a corpse away from the electric chair. Someone asks, “Why did the governor say we’re doing this?” The other replies: “To make it clear that we value human life.”

Mr. Wright was also a five-time Pulitzer Prize finalist and the author of three books, including “Wright On! A Collection of Political Cartoons’ (1971) and ‘Wright Side Up’ (1981).

His cartoons were first published by The Washington Star, then by the New York Times, and finally by Tribune Media Services.

For all the ink, toner and crayon he painstakingly combined on a late-night illustration board in his quest to penetrate celebrities in politics, sports and beyond, Mr. Wright often said that the single cartoon that caused the strongest response from readers was an emotional one designed after Walt Disney’s death in 1966. It depicts Mickey Mouse and other Disney characters in tears.

Mr. Disney’s widow, Lillian Disney, requested Mr. Wright’s original drawing for the cartoon and, when she died in 1997, bequeathed it to the Library of Congress.

In 1989, The New Yorker reported that Mr. Wright was among several American cartoonists whose work had helped inspire Chinese intellectuals and businessmen in their support for that year’s student uprising in Tiananmen Square.

Donald Conway Wright was born on January 23, 1934 in Los Angeles to Charles and Evelyn (Ohlberg) Wright. His father was an airline maintenance supervisor and his mother managed the household.

The family moved to Florida when Don was a child. He always liked to draw, and after graduating from Edison High School in Miami in 1952, he applied for a job in the art department of The Miami News. Instead, even though he was already in love with cartoons, the paper hired him for the photography department and gave him a camera.

He went on to capture classic images of a triumphant Fidel Castro entering Havana, a screeching Elvis Presley, an imposing Cassius Clay in a Miami Beach gym before he converted to Islam and changed his name to Muhammad Ali, and an ambitious Senator John F. Kennedy. in a hotel room wearing a jacket, tie and boxer shorts.

Self-taught as both a photographer and an illustrator, Mr. Wright combined a photographer’s skill and attention to detail with an illustrator’s creativity.

“He was always drawing, always sketching,” recalled Mrs. Wright, his wife, who was a reporter at The Miami News when they met.

After serving in the Army, Mr. Wright returned to The Miami News and, when the paper’s editors worried he would leave if he wasn’t transferred, began publishing some of his cartoons and assigned him to the art department as graphics editor. . By 1963 his cartoons appeared regularly on the editorial page.

In 1989 he was hired by The Post, which, like The News, was owned by Cox Newspapers.

In addition to his wife, Mr. Knight also has a younger brother, David.

Mr. Wright acknowledged that it wasn’t all his cartoons.

“You’re on a deadline,” he told the Times in 1994, “and you have three ideas, and you throw away the first one, you throw away the second one, and you’re running out of time, and before you know it, the cliche looks better.”

When he retired from The Post, he explained that although his cartoons often packed a punch, his aim was not to be humorous.

“Sometimes I’m baffled by the number of readers who think cartoons should be light and fun ‘funny,'” Mr. Wright said. “Humor has many relatives – rabid, insensitive, low and even black – aimed at the never-ending war in Iraq, incompetent and corrupt politicians, rising unemployment, the recession, Americans losing their homes and on and on.”

“But think about it for a moment,” he added. “How funny are these?”