If the economy is slowing down, no one told the labor market.

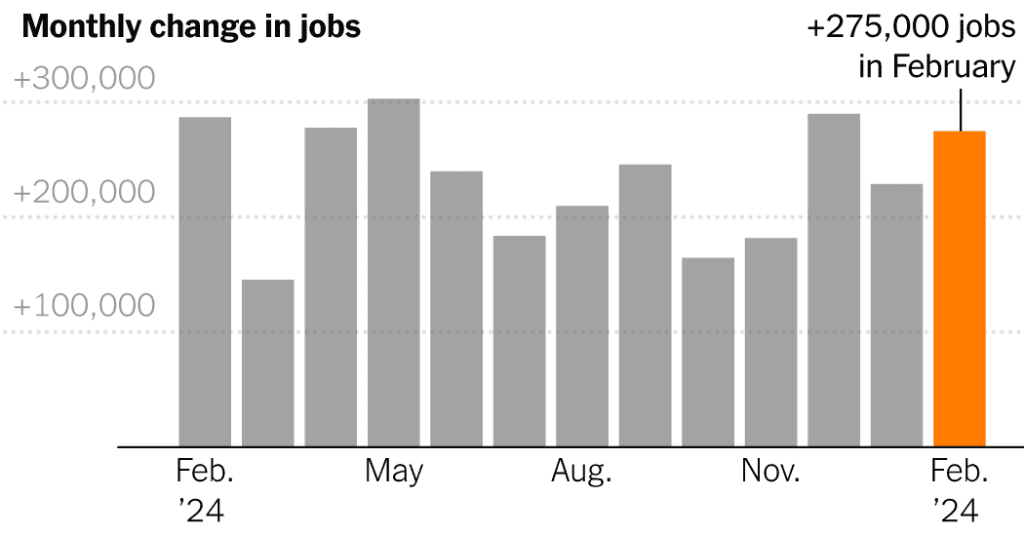

Employers added 275,000 jobs in February, the Labor Department said on Friday, in another month that beat expectations.

It was the third straight month of gains above 200,000 and the 38th straight month of growth — fresh evidence that after recovering from pandemic shutdowns, America’s jobs engine still has plenty of steam.

“We expected a slowdown in the labor market, a further easing of conditions, but we’re just not seeing it,” said Rubeela Farooqi, chief economist at High Frequency Economics.

The previous two months, December and January, were revised down by a total of 167,000 jobs, reflecting the highest degree of statistical volatility in the winter months. This does not disturb the picture of constant strong increases, which now looks slightly smoother.

At the same time, the unemployment rate, based on a survey of households, rose to a two-year high of 3.9 percent, from 3.7 percent in January. A more expansive measure of slack labor market conditions, which includes people who work part-time and prefer to work full-time, rose steadily and now stands at 7.3 percent.

The unemployment rate was driven by people losing or leaving their jobs, as well as people entering the labor force to look for work. The labor force participation rate for people in their prime working years — ages 25 to 54 — jumped to 83.5 percent, matching a level from last year that was the highest since the early 2000s.

Average hourly earnings rose 4.3 percent over the year, though the pace of increases has moderated.

“Recently we’ve seen gains in real wages and that’s encouraged people to get back into the labor market, and that’s a good development for workers,” said Kory Kantenga, senior economist at job search site LinkedIn. As wage growth slows, he said, the likelihood that more people will start looking for work decreases.

Until last fall, economists were predicting much more modest job gains, with hiring concentrated in a few industries. But while some industries swelled by the pandemic have lost jobs, expected declines in sectors such as construction have not materialized. Rising wages, attractive benefits and more flexible work hours have drawn millions of workers to the sidelines.

Increased levels of immigration have also added to the labor supply. The inflow has roughly doubled the number of jobs the economy could add per month in 2024 without putting upward pressure on inflation, to between 160,000 and 200,000, according to an analysis by the Brookings Institution.

Health care and government again led payroll gains in February, while construction continued its steady increase. Retail trade and transportation and warehousing, which had been flat to negative in recent months, rose.

No major industry lost a significant number of jobs. Credit intermediation continued its downward slide — the sector, which mainly includes commercial banking, has lost about 123,000 jobs since the start of 2021.

That’s not to say the employment landscape looks rosy for everyone. Employee confidence, as measured by company review site Glassdoor, has been steadily declining as layoffs at tech and media companies have hit the headlines. This is especially true in occupations such as human resources and consulting, while those in occupations that require personal work – such as health care, construction and manufacturing – are more optimistic.

“It’s a two-way job market,” said Aaron Terrazas, Glassdoor’s chief economist, noting that the job search takes longer for people with a bachelor’s degree. “For skilled workers in risk-intensive industries, anyone who’s been laid off has a hard time finding new jobs, while if you’re a front-line or service worker, it’s still competitive.”

The past few months have been packed with strong economic data, prompting analysts surveyed by the National Association for Business Economics to raise their forecasts for gross domestic product and lower their expectations for the unemployment trajectory. It came even as inflation has eased, prompting the Federal Reserve to telegraph its plans to cut interest rates sometime this year, further boosting growth expectations.

Mervin Jebaraj, director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Arkansas, helped record the survey responses. He said the mood was partly driven by waning concern about federal government shutdowns and draconian budget cuts, after several calls since the fall. And he sees no obvious reason for the recovery to end anytime soon.

“Once it starts going, it keeps going,” Mr Jebaraj said. “You had that external incentive with all the trillions of dollars of government spending, now it’s kind of self-sustaining, even though the money’s gone.”