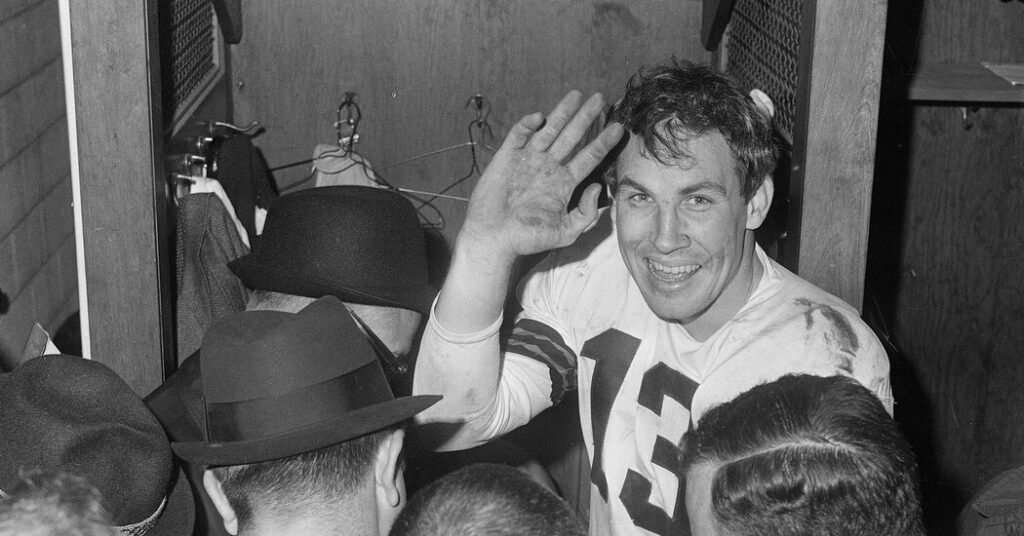

In his 13-year NFL career, Frank Ryan passed for 149 touchdowns, went to the Pro Bowl three times and led the Cleveland Browns to the 1964 NFL championship, throwing three second-half touchdowns in that victory.

It was the last time the city of Cleveland would have a major professional championship for 52 years, until June 2016, when the Cavaliers defeated the Golden State Warriors to capture the NBA title. Browns fans are still waiting for a Super Bowl win.

But when Ryan died Monday at 87, he was also remembered for his accomplishments off the football field.

Six months after the Browns’ 27-0 championship victory over the Baltimore Colts, Ryan earned a doctorate in mathematics from Rice University in Houston, where he was a quarterback.

He was a math professor at Case Institute of Technology (now Case Western Reserve University) in Cleveland while playing for the Browns and later taught math at Yale and Rice. He introduced the world of computers to the traditional United States House of Representatives and created an electronic voting system there as director of information systems for much of the 1970s, heading a staff of more than 200. He was the athletic director at Yale for 10 years and later a senior administrator for programming there and a fundraising executive for Rice.

Sportswriters were intrigued by Ryan’s different calls.

Presenting him as the general of the thinking person, they could not fail to mention the title of his doctoral thesis: “A Characterization of the Set of Asymptotic Values of a Function Holomorphic in the Unit Disc”.

Ryan said he couldn’t explain what that meant to anyone who didn’t understand advanced math, but dismissed suggestions he was a genius whose intellect helped him find weaknesses in defensive alignments on Sunday football.

“An analytical mind can certainly help a general,” he told Roger Kahn of The Saturday Evening Post in 1965. “But people who say a mathematical mind is important are not very well informed about mathematics. What I do in college has nothing to do with what I do on the field.”

His son Frank B. Ryan Jr., who is known as Pancho, said Ryan died of complications from Alzheimer’s disease at a health care facility in Waterford, Conn.

Francis Bill Ryan was born on July 12, 1936 in Fort Worth. He was a high school quarterback while developing an interest in physics and engineering.

He played for Rice in the Southwest Conference in 1956 and ’57, primarily backing up King Hill, who was selected by the Chicago Cardinals as the first pick in the 1958 NFL Draft. When Hill fumbled early in Rice’s Cotton Bowl game the 1958 vs. Navy, Ryan came in and threw a touchdown pass in the Owls’ 20-7 loss.

Ryan earned a degree in physics and was selected by the Los Angeles Rams in the fifth round of the draft. He pursued a master’s degree in mathematics while playing sporadically for the Rams in his first four NFL seasons.

His football career blossomed after he was traded to the Browns in 1962 and became a regular starter when their starting quarterback, Jim Ninowski, was injured.

But Ryan wasn’t allowed to think too much or improvise in his first season with Cleveland. That’s because Paul Brown, the team’s founder and coach, used a “messenger” system in which he rotates guards to tell the quarterback what plays he wants, with no deviation allowed.

“I didn’t turn off the math during the season, but it did reduce it,” Ryan told Sports Illustrated. “I remember Brown once saying, ‘Ryan, you sure sharpen your pencil better in football.’

Blanton Collier, who succeeded Brown as head coach in 1963, allowed Ryan significant input into game planning, and Ryan took the Browns to the playoffs four times in his seven seasons with them, emerging as one of the NFL’s most accurate passers while he was capable of releasing long throws.

After the 1964 championship game, in which running back Jim Brown ran for 114 yards to complete Ryan’s three touchdown passes to receiver Gary Collins, Ryan took the Browns to the title game for the second consecutive season, but they were defeated by Green Bay of coach Vince Lombardi. Packers.

At 6 feet 3 inches and 200 pounds, Ryan had an ideal frame for a professional quarterback of his era, though he had turned gray prematurely, perhaps giving him the aura of the respectable academic he would become. He studied game film carefully but also blended into the camaraderie of his teammates, though his life off the field was decidedly strange for a professional football player.

Ryan was released by the Browns after the 1968 season, then joined the Washington Redskins (now the Washington Governors), who had hired Lombardi as their coach and general manager. Ryan spent two seasons as Sonny Jurgensen’s backup, seeing only brief action, the first year under Lombardi and the second season for manager Bill Austin after Lombardi died of cancer in September 1970.

Ryan retired with 16,042 career passing yards and a 51.1 percent completion percentage. He was voted to the Pro Bowl every season from 1964 to 1966. And he led the NFL in touchdown passes in 1964, with 25, and in 1966, with 29.

In addition to his son Frank, he is survived by his wife of 65 years, Joan Ryan, a former sports columnist for The Cleveland Plain Dealer and The Washington Post; three other sons, Michael, Stuart and Heberden; a sister, Patricia Ryan; 11 grandchildren; and a great-grandchild, with another “on the way,” his son Frank said. A brother, Robert W. Ryan Jr., preceded him in death.

Ryan had lived for many years in Grafton, Vt., before moving to the Connecticut health facility.

Ryan donated his brain to Boston University’s CTE Center, which studies chronic traumatic encephalopathy, an Alzheimer’s-like brain disorder caused by repeated head injuries that has been linked to football and other contact sports. His family said in a statement that they suspect CTE may have “played a role” in Ryan’s condition.

“There’s a lot of exploitation in football, a lot of misdirection about what the real values are to live, to do,” Ryan told Peter Richmond for the Sports on Earth website in 2013, reflecting on his dual career and the world of big ones. time college football. “I’m not saying we shouldn’t have football in all its glory, but players need to be focused on more than just running a 4.5 forty.”

Bernard Maugham contributed to the report.