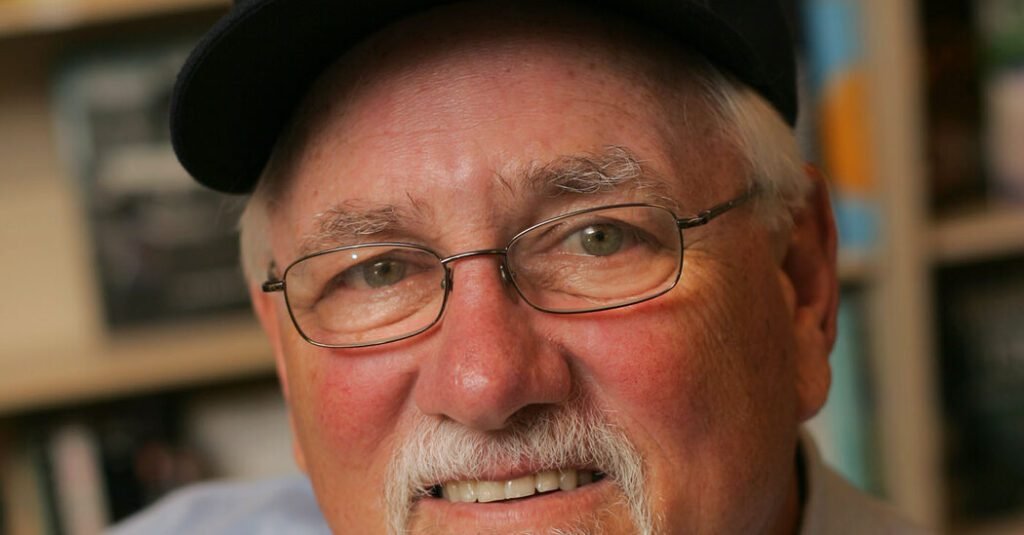

Fritz Peterson, who was a steady pitcher for the ineffective Yankees in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but whose lingering fame stemmed more from one of baseball’s most infamous “commodities”—the trade his wife with a teammate – died. He was 82 years old.

His death was announced Friday by Northern Illinois University, his alma mater and the Yankees. No release said when or where he died or the cause.

Peterson had previously battled prostate cancer and in 2018 revealed in an interview with the New York Post and in a Facebook post that he had Alzheimer’s disease.

Peterson had the misfortune of joining the Yankees in 1966, when the team finished last in a 10-team American League, near the beginning of one of the most miserable stretches in team history. In his eight full seasons in New York, the Yankees never finished higher than second place and managed to win more than they lost just four times. Mickey Mandle, the last vestige of enduring Yankee glory, has retired. Bronx attendance fell to its lowest level since World War II shortly before George Steinbrenner and other investors bought the team from CBS, which sold it at a loss, for $10 million, essentially a pittance.

In this dark time, Peterson was a leading light. Sharing the top of the rotation with another hapless Yankee, Mel Stottlemyre (who had at least gotten to pitch on the winning 1964 team), Peterson won 109 games, including 20 in 1970, when he made his only All-Star team . and averaged more than 17 wins over a four-year stretch from 1969 to 1972.

A left-hander, he didn’t get past hitters. But he changed gears effectively, using a variation on a changeup called a palm ball, and had excellent control. He had the fewest walks per nine innings in the American League for five straight seasons. For his career he averaged just 1.7 walks per game.

He was also known as a prankster who enjoyed the boyishness that flourished in the locker room. On the road with the Yankees, he stayed briefly with Jim Bouton, the pitcher and baseball icon who would later become best known for his memoir “Ball Four.” The book undermined their friendship, but before that they were partners in mischief at the club. they once loaded their toupee-wearing teammate Joe Pepitone’s hair dryer with talcum powder.

Peterson’s own memoir, “Mickey Mantle Is Going to Heaven” (2009), is one of the strangest artifacts of baseball literature. A mix of narrative—from the field and from the meandering path of Peterson’s journey into Christian evangelism—ends several chapters speculating about which of Peterson’s former teammates would go to heaven (Mantle and Bobby Murcer) and which would not (Bouton). .

But none of Peterson’s on-field accomplishments or off-field antics proved as memorable as the revelation, in March 1973, that he and another Yankee pitcher, Mike Kekich, were living in each other’s homes with the wife and each other’s children. As The Daily News headline stated, “2 Yank Pitchers Trade Wives: Peterson, Kekich Hurl Change-Ups.”

The two men, who each had two young children, had known each other since 1969, after Kekic was traded to the Yankees from the Los Angeles Dodgers. They had become close friends, met each other’s wives, and by the summer of 1972 were discussing the obvious fact that Peterson and Susanne Kekich had fallen in love, as had Kekich and Marilyn Peterson. Their solution was for the men to switch not just spouses but families, with the Kekics’ daughters Kristen, 5, and Regan, 2, joining their mother in the Peterson home and the Petersons’ sons Greg, 5 and Eric, 2, moving in with Kekic. In interviews at the time, both couples said the so-called scandal was hardly scandalous. “It wasn’t a wife swap,” Kekic said. “It was a life changer. We are not saying we are right and everyone who thinks we are wrong is wrong. That’s just how we felt.”

Mike Kekich and Marilyn Peterson’s relationship broke up shortly after it went public. Fritz Peterson and Susanne Kekich were married in 1974 and stayed that way. She survives him. Complete information on the survivors was not immediately available.

Fritz Peterson was born Fred Ingels Peterson in Chicago on February 8, 1942, the oldest of three children of Fred and Annette (Ingels) Peterson. His father was a switchboard installer for the local telephone company. his mother supervised the household.

The family lived for a time in Crystal Lake, Ill., northwest of Chicago, and Fred went to high school in Arlington Heights, Ill., where he played hockey as well as baseball. He attended Northern Illinois University, where he starred as a pitcher, earning a bachelor’s degree in 1965, two years after signing with the Yankees and playing the first of three minor league seasons.

On April 15, 1966, in his major league debut, Peterson led the Yankees to their first win of the season, beating the Baltimore Orioles.

He went 12-11 his rookie year for a team whose record was a dismal 70-89-1. The following off-season, 1972-73, as the Peterson and Kekich marriages interacted, Peterson worked as a radio commentator for the New York Raiders of the short-lived World Hockey Association. That winter, the Yankees were purchased by Steinbrenner, a businessman who insisted that his players represent the team cleanly.

After the families were traded, Kekich was traded to Cleveland in June, and Peterson was booed by fans throughout 1973 before he, too, was shipped to Cleveland in April 1974.

He spent just over two seasons there and finished his career in 1976 with a brief stint with the Texas Rangers. His overall win-loss record was 133-131, with a 3.30 earned run average.

In his post-baseball career, Peterson was an insurance salesman and blackjack dealer and wrote two other books: “The Art of De-Conditioning: Eating Your Way to Heaven,” a satire of diet and exercise regimens, and “When the Yankees Were on the ‘Fritz’: Revisiting the ‘Horace Clarke Era,’” a reference to the infielder who came to personify the mediocre Yankee teams on which Peterson played.

It was, of course, Peterson’s time.