It’s hard to imagine now, after six Super Bowl titles and two decades at the top of the NFL, but for most of their existence the New England Patriots have been awful.

The team had no permanent home for its first decade, then left Boston in 1971 for the windswept Schaefer Stadium in Foxboro. The owners struggled and went into debt. Brief moments of victory, including two Super Bowl appearances in the last century, have been punctuated by years of defeat.

The franchise’s fortunes began to change in 1994 when Robert K. Kraft, a local businessman and longtime Patriots season ticket holder, purchased the team. His first few years as president were rocky, but in 2000 he hired Bill Belichick, a coach who doubled as de facto general manager and drafted quarterback Tom Brady in the sixth round.

The trio created one of the most successful dynasties in sports and the third most valuable franchise, worth an estimated $7 billion. They joined the rarefied group of teams like the New York Yankees and Dallas Cowboys, internationally recognized brands synonymous with American success. While it would once have been rare to see the team’s Pat the Patriot logo south of Hartford, Brady jerseys have become a common sight in countries around the world. Kraft, in turn, became one of the NFL’s most influential owners.

“It was laughable,” said Upton Bell, the Patriots’ general manager in the 1970s and a longtime radio host in Boston. “As much as I like to think I can see far ahead, I never would have imagined this much success.”

Between 2001 and 2019, the Patriots won an astounding 76 percent of their regular-season games and went to nine Super Bowls, winning six. The amazing run has had three constants: a committed owner in Kraft, a generational quarterback in Brady, and a tactician in the taciturn Belichick.

In many ways, the era ended after the 2019 season when Brady left for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. The Patriots are 29-38 in the regular season over the four seasons since Brady left, a .433 winning percentage.

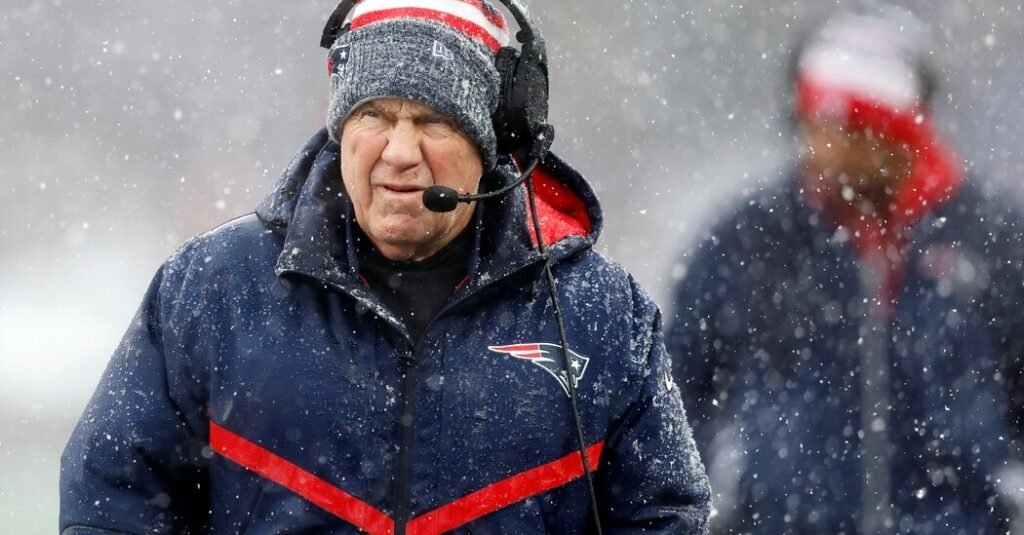

But the dynasty came to an end Thursday when the team parted ways with Belichick, 71, the second-winningest coach in NFL history. The Patriots will now have to prove they can reach the same heights on or off the field without Brady and Belichick.

“I’ll always be a Patriot,” Belichick said during a brief press conference, his voice cracking slightly. “I can’t wait to get back here, but right now, we’re going to move on.”

Although Belichick’s tenure in New England ended unceremoniously, he, Brady and Kraft will be remembered most for the wins they amassed and the way they elevated the Patriots to the highest echelons of sports.

It was especially notable that they accomplished this in the modern NFL, where teams operate under a salary cap that sets a cap on player payroll annually, with harsh penalties for teams that exceed it. This rigor forces them to constantly rebuild their rosters to compete.

“What Bill accomplished with us, in my opinion, will never be repeated,” Kraft said. “And the fact that it happened in the era of the salary cap and free agency makes it even more extraordinary.”

None of the heads of the dynasty acted alone. Kraft acknowledged that he had to step aside when it came to managing the roster. Brady was a team leader on the court and was willing to restructure his contract so that there was enough money left over to sign other players.

But Belichick has mastered the economics of the salary cap like no one else, clinically skipping over fan favorites and aging, expensive veterans in his never-ending search for what he called “value.”

Scott Pioli, the Patriots’ top player personnel officer during the team’s first three Super Bowl titles, said: “We made some decisions and we did some things we didn’t want to do, but the decisions were made because we had an obligation to others. 52 players’ and the rest of the organization.

“We’re going to make what we thought were the best decisions to have the most success,” he said.

Every team has operated under the same constraints since NFL owners instituted free agency and team salary caps, ending years of labor strife but also forcing teams to rethink how they built their rosters. Al Davis, the mischievous owner of the Los Angeles Raiders, predicted at the time that many of his brothers, who used to have most of the leverage in contract negotiations, would find this new world disorienting.

“It’s going to be like the Russians learning the free market,” Davis said of the owners and the new system.

The salary cap has toppled dynasties in big market cities like Dallas, San Francisco and Washington. Belichick and his staff, however, seemed to have a knack for finding underrated players and moxie to drain from proven stars in a sport with very high injury rates that can unsettle even the staunchest of teams.

Belichick kept the Patriots together by using a utilitarian approach to finding talented players while keeping payroll low. Kraft gave him the freedom to do so, having learned from his experience with former Patriots coach Bill Parcells, who was Belichick’s mentor. Parcells famously commented on Kraft’s involvement in his exit in 1996, saying, “If they want you to cook dinner, at least they should let you do some of the grocery shopping.”

Belichick’s value-driven approach began his first year in Foxborough when he selected the unheralded Brady in the sixth round of the 2000 draft even though Kraft was beaten by quarterback Drew Bledsoe and helped negotiate a 10-year, $103 million contract extension dollars with him at the beginning. 2001.

After Bledsoe was injured early that season, Belichick quickly turned to Brady, who led the Patriots to their first Super Bowl victory in 2002. Bledsoe and his mammoth contract left the following year. In 2003, Belichick cut defensive back Attorney Milloy, team captain, days before the season opener after he refused to take a pay cut. The message was crystal clear: Anyone could be replaced.

The NFL’s salary cap was introduced during Belichick’s first stint as head coach, with the Cleveland Browns, but it took time to master. After Belichick arrived in New England, he asked Pioli and Ernie Adams, the team’s director of football research, to create a new grading scale for player scouting that incorporated the relative value of each position and factored in a player’s versatility. They also began to link incentives in player contracts not only to individual statistics but also to team success.

The Patriots’ championship-first roster was built with the help of good drafting and the signings of many underrated free agents. In 2001, Pioli recalls committing a relatively paltry sum, about $2.5 million, in bonuses to sign nearly a dozen veteran players.

“We were signing all these guys who we knew were good players but nobody else really wanted,” he said. “If you go back to the articles, people were laughing out loud at us in the media and saying we were in this bargain basement, discount shopping.”

After a brief lull in 2008, when Brady was injured and the Patriots missed the playoffs, Belichick’s teams renewed their dominance, winning three more Super Bowls. Belichick continued to move away from players before their skills began to decline or they needed a big payday. He stunned the league by trading for defensive lineman Richard Seymour in 2009 and offensive guard Logan Mankins in 2013. He also recognized the potential in undersized and unknown players like Wes Welker and Julian Edelman, who became star receivers playing mostly out of the under valuable slot position.

“I’ve never in my entire life been around anyone in the football business who had that unique, rare combination of winning insight and foresight,” said Charlie Weiss, the former Notre Dame and Kansas coach who served as coordinator Belichick’s offense from 2000-4.

The knowledge showed in the way he guided his team each week, creating specific game plans that exploited an opponent’s specific weaknesses. Foresight was building his team with not just the current season in mind, but an eye toward the future, understanding that the salary cap era required.

“How many teams are one-year wonders?” Weiss said. “They’ll go all in for a year and then shortly after that they fall off the cliff very quickly. Well, that’s not what he did. He built a team that could stand the test of time.”

As Belichick’s teams have floundered without Brady, critics have downplayed the coach’s role in the team’s success. But wins don’t lie, and Belichick has delivered, turning the once moribund Patriots into a valuable franchise to be reckoned with on and off the field.