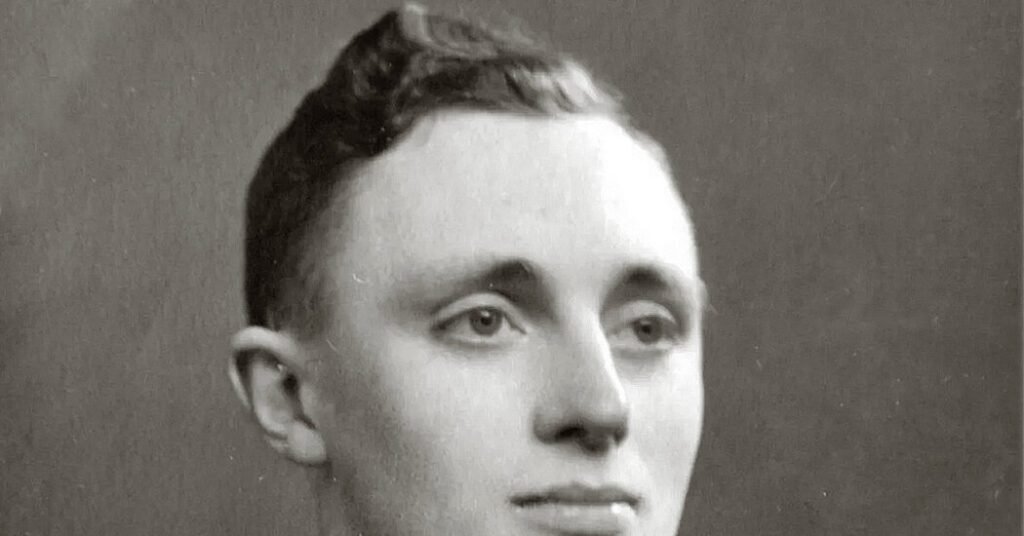

Jack Jennings, a British prisoner of war during World War II who worked as a slave laborer on the Burma Railway, the approximately 250-mile Japanese military construction project that inspired a novel and the Academy Award-winning film “The Bridge on the River Kwai,” died on January 19 in St. Marychurch of Torquay, England. It was 104.

His son-in-law Paul Barrett confirmed his death, in a nursing facility, in an email.

They said they believed their father was the last survivor of some 85,000 British, Australian and Indian soldiers captured when the British colony of Singapore fell to Japanese forces in February 1942.

A private in the 1st Cambridgeshire Battalion, Mr Jennings spent the next three and a half years as a prisoner of war, first at Changi Prison in Singapore and then in primitive camps along the railway route between Thailand and Burma (now Myanmar).

To build bridges, Mr. Jennings and at least 60,000 POWs — and thousands more local prisoners — were forced to cut and peel trees, saw them down to half a meter, dig and carry earth to build embankments and piles on the ground. .

In his 2011 memoir, Prisoner Without a Crime, Mr. Jennings described the dangerous process of driving the stakes, using a heavy weight that the men lifted atop a wooden frame.

“Two men generally guided the pile from a perched situation near the summit,” he wrote. “This was slow, punishing work, jolting your whole body when the weight suddenly dropped and the pile sank lower.”

It survived the heat of the Indochinese jungle. a daily diet of rice, watery porridge and a teaspoon of sugar. and a host of ailments: malnutrition, dysentery, malaria and renal colic. She developed a leg ulcer that required skin grafts, which were done without anesthesia.

“At least 15 soldiers were dying every day from malaria and cholera,” Mr Jennings told British newspaper The Mirror in 2019. “I remember sitting in the camp and just counting the days I had left to live. I didn’t think I’d ever get out of there alive.”

The brutality practiced by the Japanese soldiers was at least as bad during the railway works as it was in the camps.

“If you didn’t work as they thought you should, you would get a stick or the stock of a rifle,” he added. “But I had to go on. I had a friend sleeping next to me. I woke up one morning and he was dead.” Four men who tried to escape were beheaded.

“My feelings for the Japanese guards who were with us, and all who allowed them to commit such barbaric crimes, remain the same,” Mr. Jennings wrote. “I will never forgive nor forget.”

Amid these torturous conditions, Mr Jennings, who had worked as a carpenter in England, carved a chessboard from wood he found in the camps, using a penknife. He took the chess pieces home.

Jack Jennings was born on March 10, 1919 and grew up in the West Midlands of England. His father, Joseph, a bricklayer, died of cancer when Jack was 8 years old. His mother, Ethel (Dunn) Jennings, who had worked in a foundry before having children, took up laundry to earn money after her husband’s death. He also picked hops during the summer, along with Jack and his two sisters.

At his mother’s request, Jack left school at 14 to earn money for the family. He did poorly as an office intern before finding his apprenticeship at a local carpentry shop. He eventually enrolled in cabinet-making classes at a local art college.

Mr. Jennings enlisted in the British Army in 1939 and, after extensive training, traveled by boat to Singapore, arriving in January 1942. The British Army was soon overwhelmed by the Japanese and surrendered Singapore on 15 February.

“They knew where to hit and hit hard,” he wrote in his memoirs, adding that “there was nowhere to hide or retreat. We were trapped, civilians and soldiers.”

The Japanese gathered about 500 soldiers, most of them from the Cambridgeshire Regiment, on a tennis court. At each corner a Japanese soldier stood guard with a machine gun. The prisoners drank dirty water and ate “hard army biscuits and ration chocolate” thrown to them by their captors, Mr Jennings wrote.

After five days, they were taken to Changi Prison and later to prison camps that the prisoners themselves had to drive out of the jungle. Mr. Jennings said he spent his time building bridges and was cured of his ailments. An estimated 12,000 to 16,000 POWs died during the construction of the railroad. Many civilian prisoners also perished.

Mr Jennings learned of the Japanese surrender in August 1945 from leaflets dropped in a prison camp which read: “To all Allied Prisoners of War: The Japanese Forces have surrendered unconditionally and the war is over”.

He arrived home in October and, two months later, married his girlfriend, Mary. Three days later, he celebrated his first Christmas with his family in six years.

In 1954, Pierre Boulle, a former French soldier and secret agent who had served in China, Burma and Indochina, published “The Bridge Over the River Kwai,” a novel about the construction of a bridge by Allied prisoners. It was made into a film in 1957 starring Alec Guinness, as the delusional colonel in charge of British prisoners in a Japanese prison camp, and William Holden, as a US naval commander who escapes from the camp and joins a commando mission to destroy the bridge. . The film, directed by David Lean, won seven Oscars, including Best Picture.

Mr. Jennings is survived by his daughters, Hazel Heath and Carol Barrett; three grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

Mr Jennings wrote his memoirs in the early 1990s, although it would not be published until years later. He made several trips back to Singapore and Thailand.

One of them, in 2012 in Thailand, near the Burmese border, was paid for by Britain’s National Lottery, which produced a TV advert featuring Mr Jennings for a campaign called “Life Changes”.

In it he is seen walking slowly with his cane through a re-enactment of a jungle battle scene meant to haunt his memories, which fades to a visit to a cemetery for Allied soldiers who died building the railway.

“We let him have his own private time amidst the vast cemetery,” John Hillcoat, who directed the ad, wrote in an email. “It was scary how many died. Jack seemed to carry a lot of survivor’s guilt.”

In an interview with the National Lottery, Mr Jennings said the Thailand he visited was “completely different” to what he remembered. “So the old dreams just faded away, you know – so I was surprised and relieved,” he said. “The place is really a nice tourist area now.”