Patti Astor, downtown Manhattan’s “It” girl, indie film star and co-founder of Fun Gallery, the seedy East Village shop that in the early 1980s nurtured young graffiti artists such as Futura2000, Zephyr, Lee Quinones, Lady Pink and Fab 5 Freddy, who also introduced artists such as Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf and Jean-Michel Basquiat, died on April 9 at her home in Hermosa Beach, California. He was 74 years old.

Her death was confirmed by Richard Roth, his friend. No reason was given.

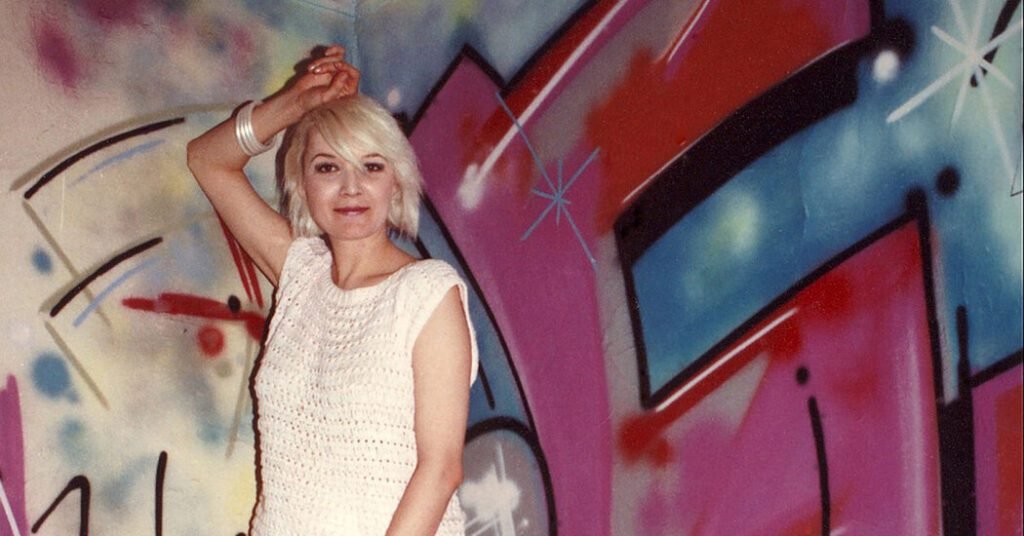

With her platinum hair, cracking voice and sparkling ’50s-style dresses, Ms. Astor was a formidable presence among the music, film and art makers gathered at the Mudd Club in TriBeCa. In the summer of 1981, one of her nightclub buddies, Bill Stelling, told her that he had rented a small storefront on East 11th Street with the thought of turning it into a gallery. Did he know any artists?

“Yes,” he said, “I know some.”

The place was only eight by 25 feet, and the idea was to make a gallery by artists, for artists. They had no money and no artistic experience, but they had many creative friends.

The first exhibition there was an exhibition of pencil drawings by Steven Kramer, Ms Astor’s husband at the time. all 20 pieces were sold, at $50 each, which seemed like a promising start. Mr. Scharf, who had already transformed all the appliances in Ms. Astor’s house into his graphic alien creatures, was offered the next show. He was also given the opportunity to name the place for his duration.

“My stuff was fun, so fun seemed like a good name,” Mr. Scharf said in a telephone interview.

Fred Brathwaite, otherwise known as Fab 5 Freddy, was show No. 3 and his plan was to call the place Serious Gallery. But by then Mrs. Astor had bought stationery stamped “Fun” and was out of money. Also, as he often said, “the name was so stupid it stuck.”

By 1982, Mr. Stelling and Ms. Astor had moved the gallery to 254 East 10th Street, an abandoned, unheated, double-wide storefront with a backyard. They built it – although the roof kept leaking and Mr. Stelling once fell through the floor – and began putting on shows by artists such as Mr. Quinones, who was already known for his street murals and art with subway cars — he famously covered 10 cars with his colorful work — and for his manifesto, “Graffiti is art, and if art is a crime, please God, forgive me.”

Fun Gallery’s grand opening was a hit, more like a block party than the white-wine affairs of a traditional white-cube gallery, as dealers and collectors around town mingled with DJs and aspiring teenage graffiti artists, brandishing their sketches.

“Patti became the first lady of graffiti art,” said Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, an art world photographer and documentary maker. “He was there before anyone else, and most importantly he understood the cultural aspect of this work at a time when the art world was very much dominated by white men.”

Fun Gallery was the East Village’s first outpost of art, and within a year or so of its opening, other homegrown galleries had begun popping up in empty storefronts. Gracie Mession, who ran a gallery out of her bathroom, moved into a space down the block from Fun. When Grace Glueck of the New York Times came to survey the scene in 1983, the gallerists called each other as she left. “Get your way,” they would say, Ms. Mansion recalls.

“It has a wild and funky configuration,” Ms. Glueck wrote, noting Fun Gallery’s bona fides as the oldest gallery in the neighborhood and its reputation for specializing in “celebrity scrappers,” as she put it, meaning graffiti artists. . He also noted that the area was still so dark that the word “merchant” had a double meaning.

“Our artists come from a different ghetto culture,” Ms. Astor told Ms. Glueck, contrasting her artists with the 57th Street gallery crowd, “and they’re also influenced by politics. they comment more on society. Their work has a new kind of beauty.”

Within two years, though, beauty was leaking out of the East Village. As their stars rose, many artists defected to SoHo galleries. The fun couldn’t compete. Mr Stelling said they were always behind on their rent and could not afford to participate in what was becoming a global market. Shipping costs to European art fairs were beyond their means. And then their friends started getting sick.

In March 1985, Lebanese artist Nicolas Moufarrege, who made intricately embroidered works of surreal and cartoon-inspired images, was hospitalized with AIDS-related pneumonia while working on his solo show for Fun. The show opened without him and he died before it ended.

The gallery closed soon after and someone tagged the windows with the words “No Mo Fun”. It had finished.

Patricia Titchener was born on March 17, 1950 in Cincinnati, the oldest of four children. Her father, James Titchener, was a psychoanalyst. Her mother, Antoinette (Baca) Titchener, was a pediatrician.

Patricia attended Barnard College in New York, where she joined Students for a Democratic Society before dropping out to devote herself full-time to the anti-war movement.

She studied at the Lee Strasberg Theater & Film Institute, but only briefly because method acting irritated her. Dreaming of stardom, she christened herself Patti Astor, inspired, she wrote in a self-published memoir, “Fun Gallery: The True Story” (2013), by Astor Place in the East Village and the euphonium of the title of a fictional street act, Patti Astor and Her Champagne Follies.

She was living in a tenement on East 10th Street when her boyfriend Eric Mitchell answered an ad that filmmaker Amos Poe had placed in The Village Voice seeking actors for a Jean-Luc Godard-like film. Ms. Astor tagged along with him, and Mr. Poe played the couple in his 1976 film “Unmade Beds,” along with Blondie’s Debbie Harry and the artist Duncan Hannah.

“I felt like I had arrived,” Ms. Astor wrote, and she dyed her hair platinum blonde to reflect the starlet she felt she was becoming. When Mr. Mitchell’s ”Underground USA,” a spin-off of ”Sunset Boulevard” starring Ms. Astor, opened in 1980 at the St. Marks, further damaged her downtown reputation.

“She was like a movie star from the 50s,” said Mr Brathwaite, who remembers asking for her autograph when he first met her at a party.

He also appeared, at her insistence, in “Wild Style” (1983), a film by Charlie Ahearn and Mr. Brathwaite about young graffiti artists, in which he played a clueless journalist reporting on the scene. It was tepidly reviewed when it came out – “‘Wild Style’ doesn’t have much of the people’s style about it, but it never saps their vitality,” Vincent Canby wrote in The Times – but in the years since its release, it has come to considered a cult classic.

Mrs. Astor’s brief marriage to Mr. Kramer ended in divorce. It leaves no immediate survivors.

After the Fun Gallery closed, Ms. Astor moved to Hermosa Beach, a trailer park surfing community, and wrote a few screenplays with her friend Anita Rosenberg. ”Assault of the Killer Bimbos” (1988), about which they wrote the story, directed by Ms. Rosenberg and in which Ms. Astor appeared, was a favorite at the Cannes Film Festival in 1987. In recent decades she has worked as a consultant and curator and historian for the street art she had helped promote, and a film about her life.

“If I were to open Fun today,” he told New York magazine in 1985, “I’d call it the Money Gallery.”

Mike Ives contributed to the report.