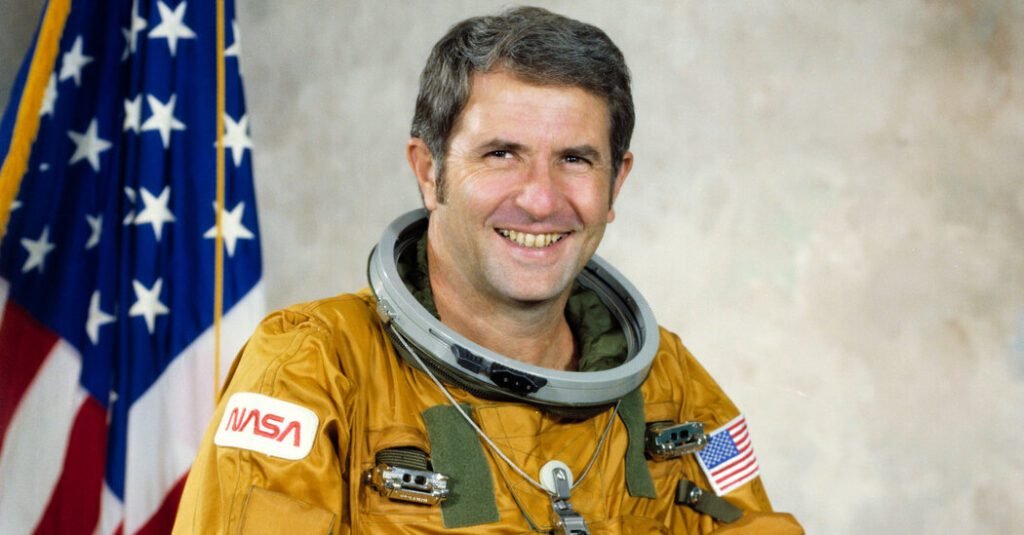

Richard Truly, a naval aviator and astronaut who flew on two early space shuttle missions and, as NASA’s associate administrator, guided the agency’s return to space after the Challenger disaster, died Feb. 27 at his home in Genesee, Colo. He was 86 years old.

The cause was atypical Parkinson’s disease, according to his wife, Colleen (Hanner) Truly.

Mr. Truly joined NASA in 1969, but did not venture into space for 12 years, when he was the pilot of the shuttle program’s second orbital flight. The success of that flight proved that NASA could safely relaunch the space shuttle Columbia, seven months after its maiden flight, and return it safely to earth.

But the mission, which was supposed to last five days, was cut to two after one of Columbia’s fuel cells failed. (That mission was separate from the 2003 Columbia disaster, which was long after Mr. Truly left NASA, and which killed a crew of seven.)

In 1983, Mr. Truly, who was captain at the time, commanded the Challenger during its third flight, the eighth overall in the shuttle program. It took off at night and landed in the dark – a first for the program. The flight also marked a personal distinction: Captain Truly was the first American grandfather in space.

Soon after, he retired from NASA to become the first commander of the Naval Space Command, which unified the Navy’s operations in space communications, navigation and surveillance.

But he returned to NASA as its associate in charge of the shuttle program in 1986, less than a month after Challenger disintegrated 73 seconds into its flight, in part due to the launch’s freezing temperatures, killing its seven-member crew, which included a teacher, Christa McAuliffe.

A month into his new job, Captain Truly said that the next shuttle would only launch in daylight and in warm weather (Challenger launched in 36 degrees Fahrenheit) and that it would land in California instead of Cape Canaveral, Florida .

“I don’t want you to think that this conservative approach, this safe approach, which I think is the right thing, is going to be a namby-pamby program,” he said. “The business of spaceflight is a bold business.”

He added: “We cannot print enough money to make it completely safe. But we will certainly correct any mistakes we may have made in the past and bring it back as soon as we can under these guidelines.”

Captain Truly was also the chairman of the internal NASA task force that provided support to the presidential commission investigating the Challenger disaster. But his primary task was to return the shuttle service to the flight.

“It was widely recognized that he did an excellent job in this responsibility,” John Logsdon, professor emeritus at the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University, said in an email.

The job took 32 months: Discovery’s launch on a four-day mission in late September 1988 created a long period of gloom and doubt for the agency.

“The nation,” Mr. Trulli, then a vice admiral, said at the time, “will have the shuttle as the backbone of its space program for the next century.”

Richard Harrison Trully was born on November 12, 1937, in Fayette, Miss. His father, James, was an attorney for the Federal Trade Commission. His mother, Jessie Smith (Sheehan) Truly, was a teacher. They divorced when Richard was young.

Mr. Truth didn’t grow up wanting to be an aviator. rather, he recalled, he dreamed of driving a fire engine. “I never really intended to be a pilot,” he said in a NASA oral history in 2003. “It never occurred to me that this would be a possibility.”

He studied engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology on a Navy ROTC scholarship and became interested in aviation during two summers of Navy and Marine Corps indoctrination. After graduating in 1959 with a degree in aeronautical engineering, he trained as a naval aviator and was assigned to a fighter squadron.

Between 1960 and 1963, he made more than 300 landings, many of them at night, on the aircraft carriers Intrepid and Enterprise and then became a flight instructor.

In 1965, it was assigned to the Air Force Manned Orbiting Laboratory, a Cold War surveillance program that planned to send astronauts into orbit in a modified Gemini capsule attached to a 50-foot-long cylindrical laboratory. But the program was canceled in June 1969, and two months later, Mr. Truly was one of seven astronauts from that program to join NASA.

He worked on capsule communications for the manned Skylab and Apollo-Soyuz missions in the 1970s, after which he became a shuttle test pilot and backup pilot for the first shuttle mission in 1981.

He left NASA shortly after his second shuttle mission when John F. Lehman Jr., the secretary of the Navy, asked him to take over the newly formed Naval Space Command in Dahlgren, Va. While there, he was promoted to rear admiral.

But after the Challenger tragedy, Mr. Lehman and the White House persuaded him to return to NASA. He recalled walking into his office on his first day as associate administrator to find people crying in the hallway “because of the hammering they’d gotten in the media,” he said in a 2012 interview at the Colorado School of Mines, where he was based. trustee at the time.

“Up until that point,” he added, “instead of a plane crash, it had been portrayed as NASA killing its crew. It was the beginning of the most tumultuous engineering, political, cultural, social endeavor I have ever been involved in.”

After three years as deputy administrator, Admiral Trulli was named administrator, the space agency’s top post, by President George H.W. Bush.

“This is the first time in its distinguished history that NASA will be led by one of its own heroes, an astronaut who has been in space,” President Bush said at a news conference.

But Admiral Truly’s three years at the top of NASA were difficult. The agency has had problems with launch delays, leaking fuel from shuttles and the discovery of a faulty mirror on the Hubble Space Telescope.

He was eventually forced to resign after clashing over NASA’s direction with Vice President Dan Quayle and his staff at the National Space Council, of which Mr. Quayle was chairman.

Mr. Logsdon said that senior NASA officials, aerospace contractors and congressional overseers had offered positive reviews of Admiral Trulli’s performance, but his tenure was viewed negatively by “those reformers who believed that NASA needed fundamental change and ended up conclusion that Truly was not the person to lead. this change”.

After leaving NASA in February 1992, Admiral Truly served as vice president and director of the Georgia Tech Research Institute, a non-profit arm of Georgia Tech, and then as director of the Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory. He retired in 2005.

His honors included the Navy Distinguished Flying Cross, the Presidential Citizens Medal, and two NASA Distinguished Service Medals.

In addition to his wife, Admiral Truly is survived by his daughter, Lee Rumbles; his sons, Mike and Dan; five grandchildren; and six great-grandchildren.

Adm. Truly admitted he was scared at times when he faced danger and technical failure as a Navy pilot and astronaut.

“Fear is a nice, healthy phenomenon,” he once said. “Any pilot who says he’s never been scared is lying.”