Ushio Amagatsu, an accomplished dancer and choreographer who brought global prominence to Butoh, an elemental minimalist Japanese dance theater form that emerged in the wake of the devastation of war, died March 25 in Odawara, Japan. It was 74.

The cause of his death, at a hospital, was heart failure, said Semimaru, a founding member of Mr. Amagatsu’s famous contemporary dance company, Sankai Juku.

Butoh is an anglicized version of “buto”, derived from “ankoku buto”, which translates to “dance of darkness”. He draws inspiration from surrealist European art movements such as Dadaism.

Butoh was pioneered by Kazuo Ohno and Tatsumi Hijikata in the late 1950s and early 60s, when Japan was still rebuilding from the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the bombing of dozens of other cities during World War II. It was part of a countercultural movement that challenged existing values as well as those flooding in from the West, Semimaru said in an email, and was an attempt to restore Japanese physicality in an unfamiliar new era.

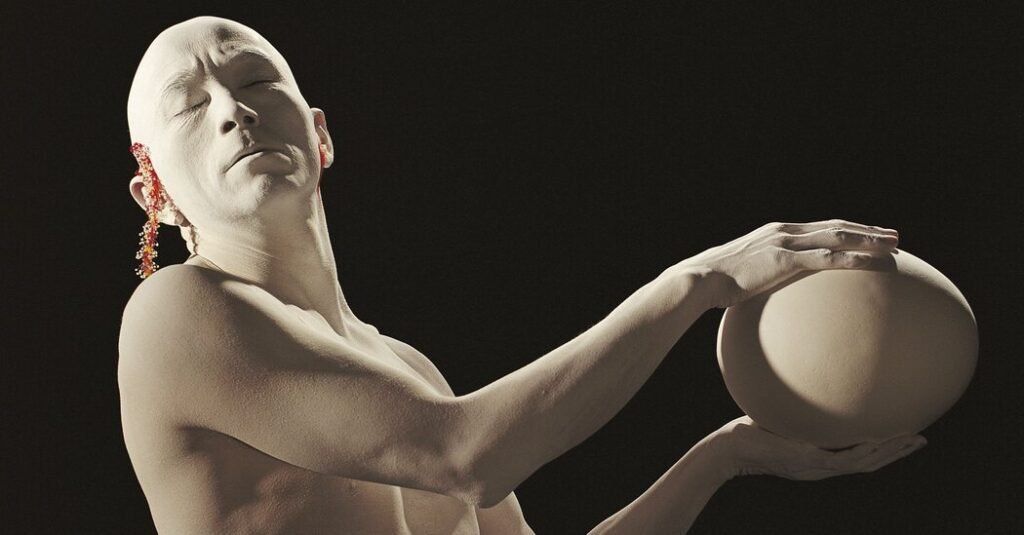

Strongly anti-traditional, Butoh rejects both Western and traditional Japanese dance aesthetics. It is performed by dancers in white body powder, symbolically erasing the personalities of individual dancers to focus on humanity as a whole. They contort their bodies and facial expressions as they explore the most primal recesses of human experience – the sexual, the grotesque, birth, evolution.

Mr. Amagatsu founded Sankai Juku in 1975 and became one of Butoh’s leading figures. Starting in 1980, the company helped spread Butoh internationally. established an ongoing production partnership with the Théâtre de la Ville in Paris in 1982 and performed in hundreds of cities in 48 countries.

“Butoh, the DNA of Japanese culture, entered European culture through Amagatsu and Sankai Juku,” wrote Akaji Maro, founder of Mr. Amagatsu’s first company, Dairakudakan, in a recent assessment in the Japanese newspaper The Asahi Shimbun, “ and Amagatsu himself. became the world standard for Butoh.”

For nearly half a century, Sankai Juku has won many accolades around the world. In 2002, he won the Laurence Olivier Award, Britain’s highest stage honor, for best new dance production, for Hibiki (Resonance From Far Away).

The company’s goal was never to comfort the public with the familiar.

“A Sankai Juku performance is infused with often spectacular moments, meticulously choreographed and carefully manipulated, that stir the emotions,” wrote Terry Trucco in a 1984 profile of the company in The New York Times. “Heads shaved and bodies dusted with rice flour, the five men of the company look uneducated, not quite human. They hiss, roll back their eyes and smile devilishly.”

“Hibiki” includes a moment in which four chalk-covered men surround a red dish of water, an allusion to blood, which is “the elixir of life” but also “a symbol of destruction,” New York critic Anna Kisselgoff . The Times wrote in its review of a 2002 performance at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

“The basic theme of all Butoh,” he added, is “destruction and creation.”

One of Mr. Amagatsu’s signature works, “Kinkan Shonen (The Kumquat Seed),” was inspired by his childhood spent by the sea. Performing in front of a wall adorned with hundreds of tuna tails, Mr. Amagatsu created movements that seemed to shrink into the figure of a boy.

Another, “Jomon Sho” (Homage to Prehistory),” was inspired by cave paintings. It begins with female dancers floating in the air, looking like masses, before descending on the stage and unfolding from the fetal position.

“‘Jomon Sho’ may begin with an image of the creation of the earth, of matter being formed,” Ms. Kieselgoff wrote in reviewing the play’s New York premiere in 1984. Before long, however, it is clear that some unnamed disaster has occurred, with Mr. Amagatsu appearing “as a helpless mutant, so jaded from our perspective that he appears to be a victim of Thalidomide.”

“The image of the bomb,” he added, “is never too far away.”

As Mr. Amagatsu told Ms. Trucco. “Providing lasting impressions is our business.”

At a more basic level, he often said, the form of Butoh was a “dialogue with gravity.”

“Dance consists of tension and relaxation of gravity, just like the beginning of life and its process,” he once said in an interview with Vogue Hommes. “An unborn baby floating inside its mother’s womb experiences the tension of gravity as soon as it is born.”

The resulting dance was often very, very slow. In a 2020 video interview, another Butoh dancer, Gadu Doushin, explained, “It’s almost like the people watching go into hypnosis — or fall asleep, whichever comes first.”

Masakazu Ueshima was born on December 31, 1949, in Yokosuka, a seaside town about 40 miles south of central Tokyo. (He later adopted his stage name at the suggestion of Mr. Maros.)

After graduating from high school, he began training in ballet and modern dance and eventually studied acting before developing an interest in Butoh. He helped found Dairakudakan in 1972. Three years later, he started Sankai Juku. The name translates to “studio of mountain and sea”, a reflection of his philosophy that human beings can learn from nature.

Mr. Amagatsu’s survivors include his daughter, Lea Ueshima, as well as a brother, a sister and two grandchildren. His marriage to Lynne Bertin ended in divorce.

Mr. Amagatsu also worked extensively outside of Sankai Juku. In 1988, for example, he created “Fushi (Homage to the Perspective to the Past)” to music by Philip Glass, at the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in Becket, Massachusetts.

He continued to perform until undergoing surgery for hypopharyngeal cancer in 2017. Even then, he continued to choreograph for his company, creating two new works, ‘Arc’ (2019) and ‘Totem’ (2023). “Kosa,” a collection of some of his best-known choreography, ran for two weeks at New York’s Joyce Theater last fall.

All along, Mr. Amagatsu believed that his choreography “depends on whether or not you can keep that ‘thread of consciousness’ unbroken,” he said in a 2009 interview with Performing Arts Network Japan. “If that thread breaks, everything is just an exercise.”