During the brutal Battle of Okinawa in Japan, in the final months of World War II, a group of American soldiers took up residence in the palace of a royal family who had left the fighting. When a palace steward returned after the war ended, he later said, the treasure was gone.

Some of those valuables turned up decades later in the attic of the Massachusetts home of a World War II veteran, whom the Federal Bureau of Investigation did not identify when announcing the find last week.

The veteran’s family discovered the cache of living paintings and vases. large fragile scrolls. and an intricate hand-drawn map after his death last year, and reported the discovery to the agency’s Art Crime Team.

Geoffrey Kelly, special agent and art theft coordinator for the bureau’s Boston office, was assigned to the case and brought the artifacts to the National Museum of Asian Art at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. The recovered items were returned to Okinawa in January, and an official repatriation ceremony is planned for next month in Japan.

“It’s an exciting moment when you see the reels unroll in front of you, and you’re just witnessing history and seeing something that not many people have seen in a long time,” he said.

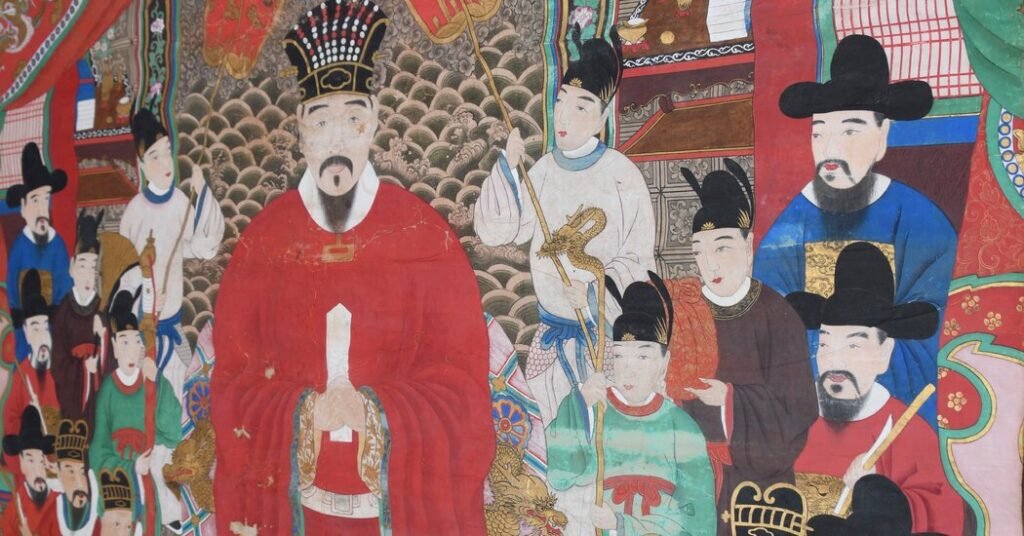

Verified by Smithsonian experts as authentic artifacts from the old Ryukyu Kingdom, a 450-year-old dynasty that ruled Okinawa as a vassal state of China’s Ming Dynasty, the FBI turned the artifacts over to the U.S. Army’s Political Affairs and Psychological Operations Command. Heritage experts returned the precious pieces to Okinawa.

“Very few objects survived from this realm,” said Travis Seifman, an associate professor at the Art Research Center at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto, Japan. “Recovering heritage, recovering cultural treasures, knowing their history is a really big deal for a lot of people in Okinawa.”

The Ryukyu Kingdom ruled Okinawa from the early 15th century until 1879, when Japan annexed the kingdom as a prefecture.

The cache of 22 items from the 18th and 19th centuries includes two portraits of Ryukyu kings – the only two of 100 painted known to have survived the war – “an incredible find”, he said.

A typewritten letter, written by a US soldier stationed in the Pacific theater during World War II, was found with the artifacts and indicated the items were taken from Okinawa, authorities said.

The letter described the smuggling of the pieces from Japan and the attempt – and failure – to sell them to a museum in the United States, said Col. Andrew Scott DeJesse, the heritage conservation officer who accompanied the artifacts back to Okinawa.

The veteran, who was deployed to Europe, found the artifacts near a trash can, Col. DeJesse said, and recognizing their value took them home to Massachusetts.

“Samurai swords, katanas, military personnel stuff, that’s always been acceptable,” Col. DeJesse said, describing how American commanders have approved service members’ war trophies from the battlefield.

During World War II, heritage researchers known as Monuments Officers were in Europe tracking down millions of works of art, books and other valuables that had been stolen by the Nazis. Officers were also stationed in Japan, “but the looting of cultural heritage sites,” Colonel DeJesse said, “wasn’t really known,” adding that Americans weren’t the only ones taking items from war zones.

“The Japanese Empire did it everywhere. So did the Nazis, so did the Soviet Union. It was done systematically,” he said.

The Battle of Okinawa, which has been described as “82 days of the costliest fighting in the Pacific”, was among the bloodiest campaigns of World War II. About 100,000 Japanese civilians and 60,000 soldiers were killed. More than 12,000 American soldiers, sailors and marines lost their lives in the three-month battle. Artwork and other valuables weren’t the only items stolen. Some researchers have said that US soldiers took skulls and other body parts as trophies.

After the war ended in 1945, Bokei Maehira, a palace steward, returned to the palace to check on the relics – which included crowns, silk robes, royal portraits and other artifacts – that he had hidden with others in a ditch in the area of the palace. . He found the palace reduced to ashes and the moat looted, he wrote in an academic paper published in 2018.

Among the spoils was “Omorosaushi,” a collection of Ryukyuan folk songs dating back centuries.

The US government repatriated the Omorosaushi to Okinawa in 1953 after an American commander, Carl W. Sternfelt, brought the spoils of war to Harvard University for evaluation.

In 1954, the United States joined dozens of other countries in signing the Hague Convention, a United Nations-brokered treaty for the protection of cultural property in armed conflict.

But Col. DeJesse, who served two tours in Afghanistan and one in Iraq, said part of his and other legacy officers’ jobs is to educate military commanders and soldiers who are unaware of that obligation.

“It’s a big problem. We advise them, “Hey, don’t touch it, don’t pick it up. It’s someone else’s. Just like you wouldn’t want your own church, your own museum to be looted,” he said.

The Japanese government listed other missing Ryukyu Kingdom artefacts in the FBI’s National Stolen Art Archive in 2001. They include black-and-white photographs depicting a collection of important Okinawan cultural heritage that, according to Professor Seifman, “in many cases are all survivals of and items lost or destroyed’ in World War II.

Among the items listed were scrolls found in the Massachusetts veteran’s attic.

The veteran’s family, who have been granted anonymity by the FBI, will not face prosecution.

“It’s not always about prosecutions and putting someone in jail,” Mr Kelly said. “A lot of what we do is to make sure that stolen property goes back to its rightful owners, even if it’s generations down the road.”